Tales From Discoverability Land: Vol. 1

A miscellany of discoverability-related goodness.

[Hi, I’m Simon Carless, and you’re reading Game Discoverability Weekly, a regular look at how people find - and buy - your video games. Or don’t. You may know me from helping to run GDC & the Independent Games Festival, and advising indie publisher No More Robots, or from my other newsletter Video Game Deep Cuts.]

So I thought I’d try a different approach for this version of Game Discoverability Weekly.

Rather than concentrate on a single major subject, I thought it might be fun to go through a few notable recent articles or factoids, and add some context or new theories. So let’s do that! Starting with:

1. How Steam users see your game (Chris Zukowski / Gamasutra)

Chris - who reads this newsletter, hi Chris! - is the extremely sharp gentleman who did a talk about email marketing at GDC 2019 which was one of the best-rated talks of the entire show.

He’s working on how to improve discoverability on his own games. He’s now moved into an area that not many people have explored - how actual Steam users browse the store and wishlist games.

The above article/videos is particularly interesting because he hit me up after my recent article about game stores needing more real-time charts, and said essentially: ‘I’m prepping an article, and it doesn’t look like people use real-time charts to pick out games much at all’. And you know - at least with his small sample size - he’s 100% right!

To my credit, I did at least put at the end of the piece: “it’s possible that we are all reading this the wrong way around - that sales actually aren’t majority affected by store placement, and we just want access to these charts to see what is happening under the surface anyway.” So now, obviously, hindsight being 20/20, etc, I think this is much closer to the truth.

But what his research does confirm is something I’ve also been talking about. Simply: ‘This game reminds me of another SUPER POPULAR game that I like’ is a key entry point for a Steam gamer.

As Chris says: “From what I saw, people know their genre and they don’t want to wishlist something with unfamiliar gameplay. They want to wishlist something they know.”

You can see this, for example, in My Time At Portia doing great with those who dug Stardew Valley. And you can see it echoed in a section of my ‘hot or not?’ piece: “So again, people played something, and they want more of that thing.”

But I think the key is in finding a genre that is super popular and doesn’t have many direct competitors to the leading games. Otherwise, sometimes it’s difficult to measure up to the top games in that genre - especially if they continue to be developed.

(Side note: Chris is also prepping a newsletter series about marketing your game, and I trust you all to keep reading mine while also reading his, so go and subscribe now!)

2. An indie game developer discovering the world of user acquisition and advertising (Frozax Games)

I haven’t really talked much about mobile games and discoverability. This blog post from Frozax - who has 900,000 downloads of their latest free-to-download game across iOS and Android - is a good example of why it’s a super tricky space.

Tents and Trees, the puzzle game Frozax is discussing, monetizes majority via ads, but also via in-game currency. And what their blog shows is that ‘paid acquisition’ of users is super tricky, because you’re competing against massive F2P titles that rely on whales & have tuned their monetization tactics with large teams.

So if you can’t afford to buy new users (because your game isn’t as good slash predatory at monetizing them), and organic reach in general isn’t what it used to be on Android and iOS, how do people find you? They… probably don’t.

Having said all that, Frozax was clearly experimenting with SUPER small volumes as a novice, so their experience may not be completely representative.

But for lots more context/info on this subject, I recommend checking out Michael Gordon’s GDC Discoverability Day talk ‘Paid Acquisition for Smartphone Games: A Scrappy, Practical Guide’.

Michael is INCREDIBLY transparent on what is generally a private subject. As someone who spends a lot (for a non-large company) monthly on user acquisition, he’s very generous in sharing a playbook for those who want to master discoverability for free mobile games. (Which is 50% or more of all video game revenue, after all.)

3 Cliffski, Production Line & Steam review ratios

This is more of a data point than a blog. But a couple of weeks back, noted UK indie Cliffski announced on Twitter that his car factory construction sim Production Line had sold 100,000 copies on Steam:

I thought this was useful data, because Cliffski is not a ‘please review my game on Steam’ type. And we could check the number of reviews (at least English-filtered ones) that the game had at that point. So, it was around 1,600 reviews for 100k sales - so 16 reviews per 1,000 sales.

I have access to data from friends and colleagues of several other titles. So I took this as a great example of how Steam reviews are APPROXIMATELY accurate as to sales, but can’t be relied on for exact detail.

For example, I know another title that has 22 reviews per 1,000 sales, and I even know of one (fan favorite) title that has 30 reviews per 1,000 sales.

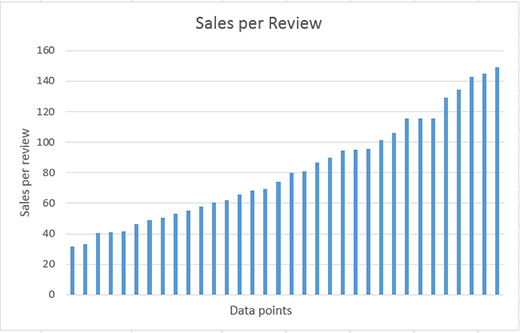

This isn’t really new information, because the ever-reliable Jake Birkett has a great 2018 article on the subject, in which he shows the large differences in sales per review:

(He’s operating on sales per review and on games launched at ANY time, whereas my above numbers are on number of reviews to get to 1,000 sales, and on newer-launched games. But you can work it out pretty easily - the three numbers I cite above are 62 sales per review, 45 sales per review and 33 sales per review.)

Anyway, my point is - based on my limited data points, it seems like a game with 1,600 reviews on Steam that launched in the last year could have sold - let’s say - anywhere between 40,000 copies or 120,000 copies. And it wouldn’t surprise me if the spread is probably wider than that still!

That’s quite a difference, estimation wise. So just make sure you think about that when you’re speculating whether people have money hats - or just money socks.

Til next time, take care,

Simon.